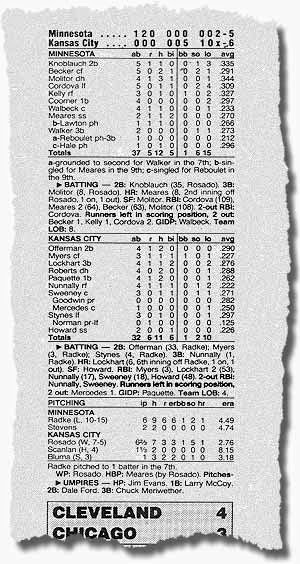

It was the top of the eighth inning in front of 52,751 spectators when Vic Wertz made his way up to the plate with two runners on against Giants reliever Don Liddle. To get an idea of how amazing this play way, I'll let the writing of John Drebinger in his article Giants Win in 10th From Indians 5-2, On Rhodes' Home Run from the September 30, 1954 edition of the New York Times tell the tale:

Wertz connected for another tremendous drive that went down the center of the field 450 feet, only to have Willie Mays make one of his amazing catches.

Traveling on the wings of the wind, Willie caught the ball directly in front of the green boarding facing the right-center bleachers and with his back still to the diamond

Here is how the newspaper captured the catch in four images:

To see the play unfold in real time, check out the following video:

Though many of today's fans will think this catch to be passé and ordinary (read the comments after the video on the YouTube page for more proof of this), this catch came at the hands of a 21-year old rookie who on the biggest sports stage of them all caught the ball with his back to the field, running full speed ahead and arcing his head back to see the ball and then fired the ball in keeping the two runs on base from scoring. I know haters are going to hate but damn.

What did Willie Mays think of this play? The interview of Willie Mays from the Academy of Achievement website has Mays telling us in his own words about this play:

I think the key to that particular play was the throw. I knew I had the ball all the time. In my mind, because I was so cocky at that particular time when I was young, whatever went in the air I felt that I could catch. That's how sure I would be about myself. When the ball went up I had no idea that I wasn't going to catch the ball. As I'm running -- I'm running backwards and I'm saying to myself, "How am I going to get this ball back into the infield?" I got halfway out. As I'm catching the ball I said, "I know how I'm going to do it." I said, "You stop..." -- I'm visualizing this as I'm running. It's hard to tell people that -- what I'm doing as I'm running. I know people say, "You can't do all that and catch a ball." I said, "Well, that's what I was doing. Okay?" I was running, I was running. I'm saying to myself, "How am I going to get this ball back in the infield? "So now as I catch the ball -- if you watch the film close -- I catch the ball, I stop immediately, I make a U-turn. Now if I catch the ball and run and turn around -- Larry Doby which is on second, Al Rosen on first -- Larry can score from second. Because Larry told me -- I didn't see this, Larry had told me many times -- "I was just about home when you caught the ball, I had to go back to second and tag up and then go to third." So he would have scored very easily. So I said, well -- as I'm running, I've got to stop and make a complete turn. You watch the film and you'll see what I'm talking about. I stopped very quickly, made a U-turn, and when I threw the ball I'm facing the wall when the ball is already in the infield. So when you talk about the catch, more things went into the play than the catch. The throw was the most important thing because only one guy advanced, and that was Larry, from second to third. Al was still on first. And that was the key. To me it was the whole World Series.Want to see a different view of the catch to see how hard it must have been for Mays? The article Photo of Day II: An uncommon angle on 'The Catch' by Willie Mays by Dayn Perry of the CBSSports Eye on Baseball page dated January 10, 2014 shows us the following view:

Folks, this is not an ordinary catch. That's all I have to say.

Until Then Keep Playing Ball,

Baseball Sisco

#baseballsisco

#baseballsiscokidstyle

For Further Reading:

- Click here to access the 1954 Cleveland Indians page from Baseball Reference.com

- Click here to access the 1954 New York Giants page from Baseball Reference.com

.jpg)